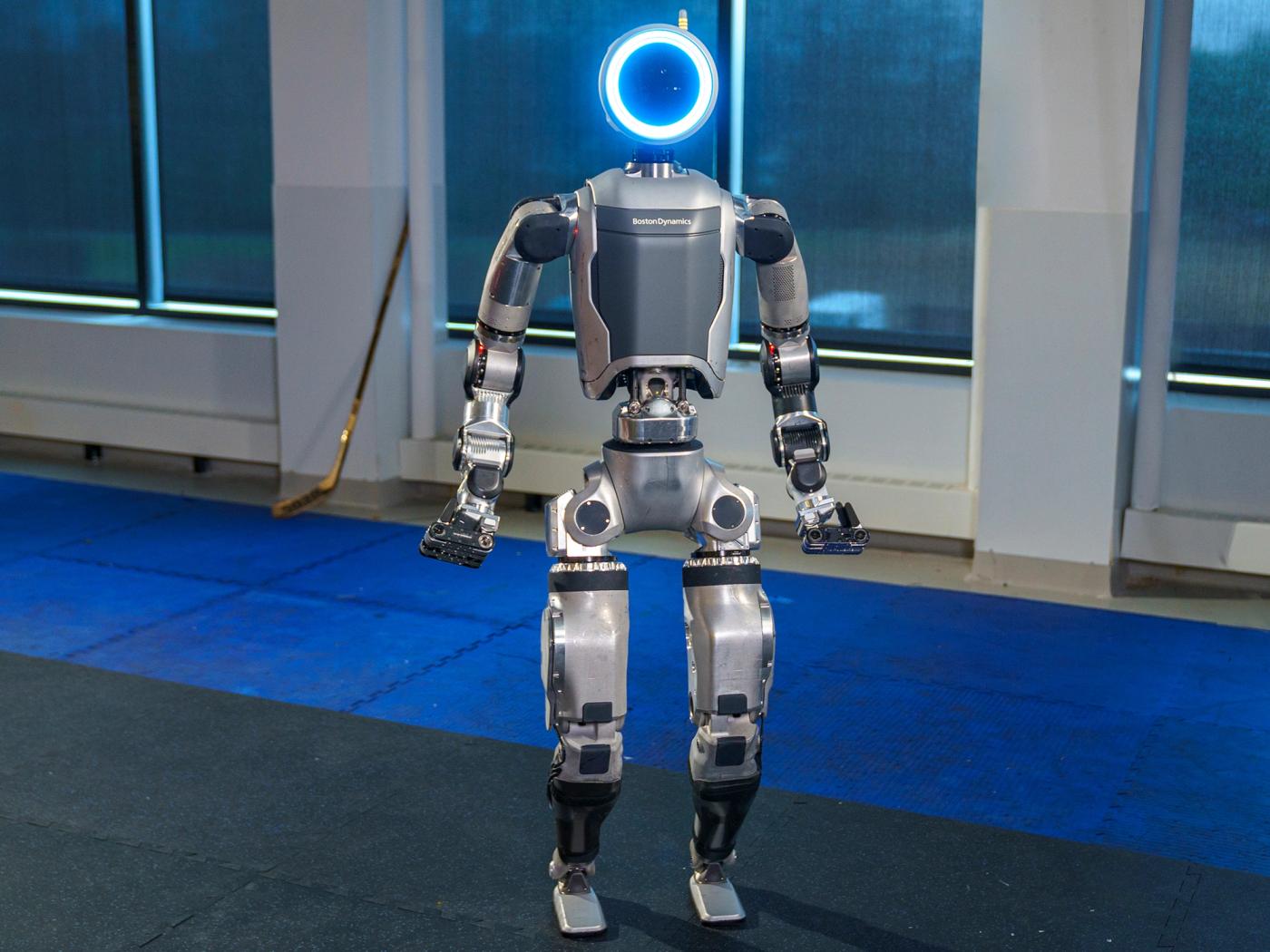

Atlas is Boston Dynamics’ flagship humanoid program. In April 2024 the company retired the hydraulic Atlas and unveiled a fully electric successor designed for real-world applications. In 2025 they described Atlas as integrating modern robot-learning pipelines (simulation + reinforcement learning) and high-performance edge compute to run complex multimodal models alongside whole-body and manipulation controllers.

Atlas is the “top end” of humanoid robotics: not because it’s the most productized today, but because it’s the clearest example of what happens when you combine decades of control expertise with modern learning. The system that matters here isn’t just the body—it’s the loop: simulate → learn policies → validate on hardware → harvest new edge cases → re-train. Boston Dynamics is unusually good at that loop, and Atlas is where they stress-test it.

The 2024 shift from hydraulics to fully electric actuation wasn’t cosmetic. It changes the operational profile: less hydraulic complexity, fewer leaks and maintenance pain points, and a cleaner path to industrial settings where “serviceability per hour” matters as much as peak athleticism. Boston Dynamics framed the new Atlas as “designed for real-world applications,” which is a strong signal that Atlas is no longer only a research mascot.

In March 2025, Boston Dynamics said Atlas is an early adopter of NVIDIA’s humanoid platform work (Isaac GR00T) and is integrating the NVIDIA Jetson Thor compute platform, with learned dexterity and locomotion policies developed using Isaac Lab (built on Isaac Sim and Omniverse). At a systems level, this tells you the direction: Atlas is moving toward a “policy-driven robot” where the brain can be updated as fast as the training pipeline, while the classical whole-body controller remains the safety-critical backbone.

Where Atlas consistently differentiates is motion quality under constraints. Most humanoids can walk; Atlas can do controlled, dynamic motion while keeping the upper body useful. That matters because industrial tasks are not “walk from A to B.” They’re “walk while carrying awkward things, avoid humans, keep balance, then manipulate an object precisely.” Atlas is built around that combined requirement.

The honest constraint: Boston Dynamics still publishes more narrative than audited, shift-level metrics. That’s normal for frontier humanoids, but it matters for readers: a robot can be extremely capable in short demonstrations and still be expensive to operate at scale if recovery, uptime, and maintenance aren’t solved. Atlas is best understood as the most advanced “capability engine” in humanoids—one that is now clearly pointed toward commercial manufacturing, especially through Hyundai.

90 / 100

82 / 100

86 / 100

70 / 100

78 / 100

67 / 100

| Spec | Details |

|---|---|

| Robot owner | Boston Dynamics (Hyundai Motor Group subsidiary) |

| Generation focus | Electric Atlas (announced April 2024 as successor to hydraulic Atlas) |

| Actuation | Fully electric (hydraulic Atlas retired; electric platform introduced as the next era) |

| Degrees of freedom (DoF) | Atlas described as 50 DoF in Boston Dynamics research communications (Aug 2025). Atlas MTS variant described as 29 DoF for manipulation-focused exploration. |

| Grippers | Research notes describe 7 DoF per gripper enabling diverse grasp strategies (power/pinch, etc.). |

| Vision | Boston Dynamics research blog references a pair of HDR stereo cameras mounted in the head for teleop awareness and policy input. |

| Onboard compute | Boston Dynamics stated Atlas is integrating NVIDIA Jetson Thor and is an early adopter of NVIDIA Isaac GR00T platform work (Mar 2025). |

| Training / learning | Learned locomotion + dexterity policies developed with NVIDIA Isaac Lab / Isaac Sim; whole-body and manipulation controllers remain central for stability and safety. |

| Speed / payload / runtime | Not publicly confirmed for electric Atlas (public numbers widely cited online largely refer to the older hydraulic Atlas era). |

| Primary deployment path | Manufacturing and industrial work, with Hyundai as a key ecosystem partner and scaling channel. |

| Public spec reliability | High for “electric transition + compute/training stack” (primary sources); medium for quantitative performance metrics (limited audited data). |

| Priority | Pick | Why | Tradeoff to accept |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best first environment | Manufacturing cells with clear safety boundaries | Factories are repeatable, measurable, and reward whole-body manipulation (carry, place, orient) more than “general” navigation. | Early success will be scaffolded (fixtures, standard bins, constrained lanes). That’s fine—just don’t confuse it with “general-purpose.” |

| Best first workload | Awkward-load handling + kitting + staging | Atlas is built to be strong and stable while moving. Kitting/staging converts that into measurable operational value quickly. | Low tolerance for drops or misplacements. Recovery and verification behaviors must be product-grade. |

| Fastest learning loop | Repetitive tasks with controlled variability | Perfect for simulation → RL → field validation cycles. Every small variation creates training signal without chaos. | Controlled variability is not “the world.” Expansion needs staged broadening of object sets and layouts. |

| Long-term bet | Multi-skill industrial humanoid | If learned policies + edge compute keep improving, Atlas can become a re-taskable worker across lines and facilities. | The last 10% is brutal: safety certification, uptime, and cost per hour decide winners more than raw capability. |

Atlas is best evaluated on “boring work” where the inputs are messy enough to test autonomy, but structured enough to prove economic value. The table below reframes cost the way operators feel it: not the sticker price, but the supervision + downtime + recovery budget required to get consistent throughput.

| Scenario | Input | Output | What it represents | Estimated cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engine/part staging | Standard totes + fixtures, clear walk lanes | Parts delivered to station, oriented correctly | Whole-body carry + precise place while staying stable near humans | Low if recovery is strong; high if drops trigger frequent human interventions |

| Kitting + replenishment | Known bins, moderate object variety | Correct kit completeness at station | Dexterity under repetition; verification and error handling dominate | Moderate: costs shift from “training” to “QA + exception handling” |

| Awkward-load transport | Large/odd parts, changing center of mass | Safe transport without collisions or near-misses | Stability + safety envelope; shows whether autonomy is real under load | High early: safety constraints slow throughput; improves as policies mature |

| Line reset / cleanup | Tools and clutter, semi-structured environment | Work area restored to known state | Navigation + manipulation + “keep going” recovery behavior | Moderate: lots of long-tail edge cases; great for data but rough for first ROI |

| Assistive handling near workers | Human coworkers, mixed tasks | Cooperative positioning/holding, handoffs | Safety authority + predictability; the trust problem becomes the bottleneck | High until safety validation and behavior predictability are proven in hours, not minutes |

Atlas can learn fast, but industrial deployment is not “let the model decide everything.” Treat learned policies as the performance layer, and keep safety as a hard boundary.

The difference between a demo robot and a workforce robot is recovery. Track it like a first-class product metric.

The fastest ROI is not “Atlas can handle anything.” The fastest ROI is “Atlas is boringly reliable in a designed workflow.”

Scaling to many robots will hinge on monitoring, updates, parts, and service response time—more than raw capability.

Hydraulics can deliver extreme power and responsiveness, but they introduce operational overhead. By retiring the hydraulic Atlas and introducing a fully electric successor, Boston Dynamics signaled a move toward “workplace-ready” practicality: cleaner operation, better serviceability, and a clearer path to industrial deployment.

Atlas is legitimately the most advanced on mobility and whole-body control. The open question is commercial readiness at scale: uptime, recovery, and total cost per productive hour. Those metrics—not acrobatics—decide who wins factories.

Boston Dynamics said it’s integrating Jetson Thor to run complex multimodal AI models on the robot, while using Isaac Lab/Sim to accelerate robot learning in physically accurate simulation. In plain terms: faster iteration on learned policies, more onboard compute to run them, and a tighter pipeline from simulation to the real robot.

Audited, shift-level numbers: mean time between interventions, mean time between failures, hours run in production-like settings, recovery success rates, and cost per deployed hour including maintenance and supervision. Until then, treat Atlas as a frontier platform that is clearly aiming at real work, but still proving economics.